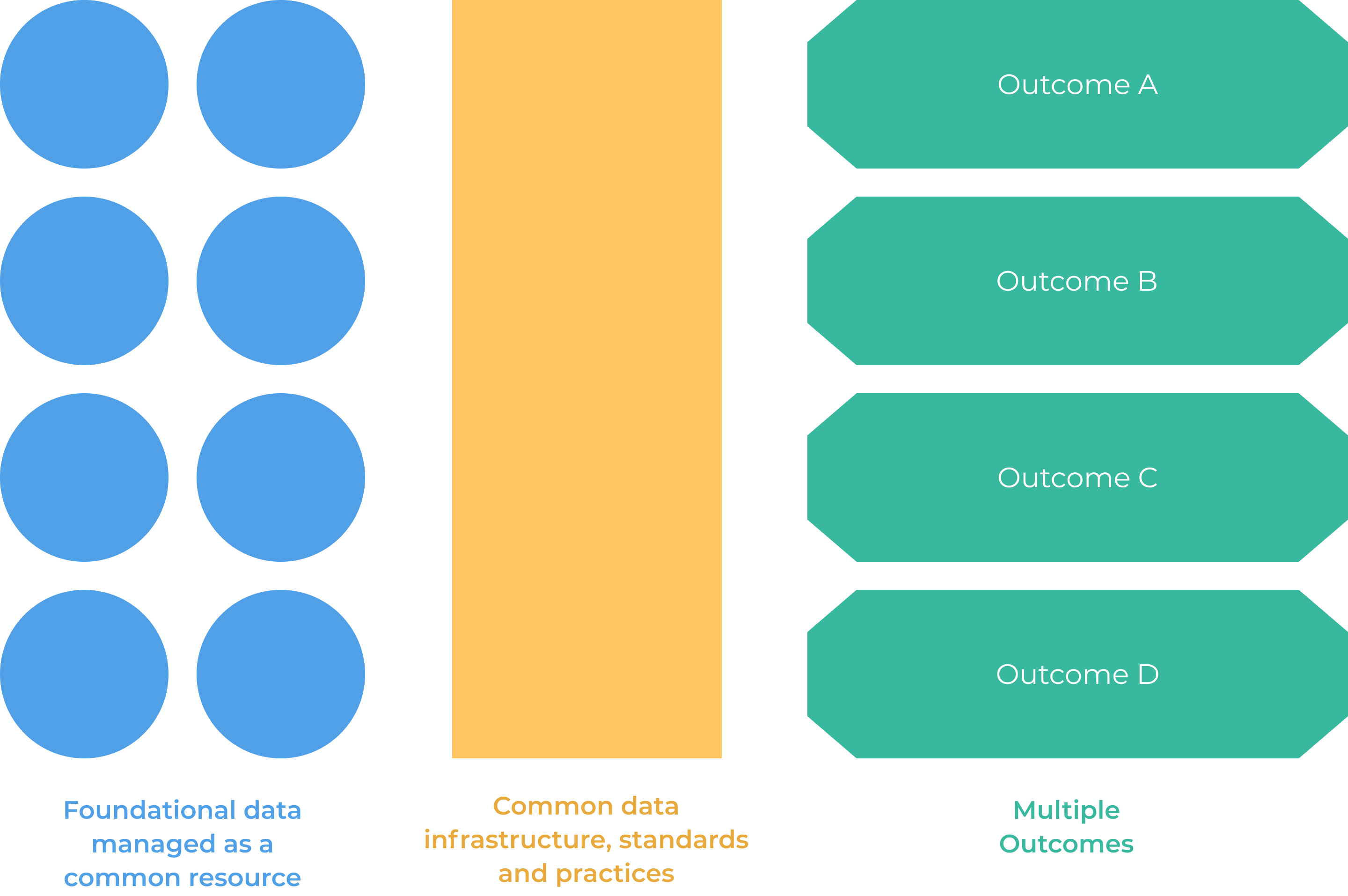

[CITY] will identify the most important datasets it needs to deliver on its vision and act to govern them as common resources across departments and agencies.

Cataloguing the [CITY]’s foundational data

Foundational data is the fundamental data within the municipal data ecosystem. Foundational data is the basic business data that is essential for the municipality’s central functions. This should be sufficient well documented to provide a common understanding of what the data is about, what it contains and where it can be found.

Without an understanding of what data exists, it is difficult, or impossible, to combine information resources reliably and efficiently, which means that the ability of the data strategy to have impact will be limited. The first step therefore is to identify the key foundational data categories required for data driven decision making and implement fixes and improvements to make sure this data is usable across the organisation. Challenges that might currently exist, and need to be addressed, are as follows (not exhaustive):

- Foundational data is missing

- Foundational data is distributed across multiple different systems

- Copies of foundational data are being used instead of the foundational data itself

- Foundational data is being manually maintained

- Identifiers, metadata is missing or not accessible

Following the approach of Estonia’s Administration system for the state information system RIHA, [CITY] will publish a list of foundational datasets documented down to the level of individual data fields. This should include only a description of the system, not any data constrained within them.

The starting point for this work should be the ‘top 25 datasets’ required for the delivery of improvements in the Strategic Priority Areas defined in the [STRATEGIC PLAN]. These should be identified by the Data Council.

Data exchange and governance

The main objectives of data governance are to ensure data quality, data security and privacy, and data accessibility, remembering that data is only an asset to [CITY] if it is used. Data management needs to be organised across [CITY] to ensure adherence to data governance standards.

In [CITY] currently, there are hundreds of different systems and technologies being used across siloed departments and units, which means different ways of storing, updating and using data. Both systems and people process data differently leading to significant data quality challenges. This further becomes problematic when this data needs to be combined for reporting, analysis and models, if it even is able to be combined. Therefore, investment in data governance, especially data quality and interoperability, will lead to a greatly improved secondary use of data, in order to promote data-driven decision making. This will also help with the ability to audit what data is being used where, for what purpose, and so ensure data is being kept secure, and where necessary, private.

Interoperability in particular enables systems, technologies, and services to seamlessly exchange data, supporting smooth interactions across departments, vendors, and external partners. This capability is especially critical for [CITY] as they’re aiming to break free from dependency on a single vendor, empowering them to select and integrate systems that best meet their evolving needs without restrictive boundaries. At its essence, interoperability ensures that [CITY]’s units can interact across data, systems, and processes to achieve cohesive public service delivery. This approach builds a flexible digital ecosystem that promotes data access and collaboration, enhancing overall efficiency and providing a foundation for growth. Interoperable digital infrastructure also opens opportunities to adopt best-in-class solutions, whether in the cloud, data analytics, or open-source tools, contributing to a more resilient, adaptable, and cost-effective municipal ecosystem.

In line with the FAIR principles, which aim to optimise the reuse of data, [CITY] Municipality’s units should also be able to find, then either access the data at source, or follow a standard process for request a copy of the data. The data should be interoperable with other datasets through the use of common standards and identifiers. Further, the governance processes for using the data should be clear.

A representation of a city technology stack. Source Richard Pope: Platformland - An anatomy of next generation public services

As shown in the figure above, in order to implement data-driven mechanisms in [CITY], it has to attain a modern technology architecture capable of organising, and surfacing, data in a way that maximises its usability and exchange. This is a challenge for the municipality given the number of systems that currently exist in its technology stack. It is also possible that some municipal data is stored in systems controlled by third parties. The core principle of the target data architecture, as in line with the FAIR model, is to make sure all [CITY]’s data is accessible via a similar mechanism. To this end, common APIs and API policies should be created and implemented. A municipality-wide data system (a data hub) should be created to interact with the systems inside municipality departments and agencies, that can act as an example as APIs within municipal departments and agencies come online.

The data group needs to work with the Information Management Unit (IMU) in creating an understanding of the “as-is” data architecture of the municipality, and designing a target architecture, ideally distributed / semi-distributed, that results in the success of the data strategy. This roadmap should be able to be implemented iteratively to ensure that the data strategy can begin to be implemented from day one, and through this, architecture begins to evolve to meet the needs of the strategy implementation.

[CITY] needs to develop common data quality metrics based on the above to enable continual data quality improvement as the municipality utilises and grows its data capabilities. These data quality standards and metrics will empower data custodians and owners to monitor current usage and improve data quality over time. This will also mean that inadequate data is not used in data analysis, resulting in less-accurate outcomes.

[CITY]’s DWG must classify data according to defined data classification standards when creating the data catalogue and data hub. Especially important will be to classify the data by its processing rules, thereby unlocking its usability throughout the organisation.

Over time this should allow [CITY] to move towards implementing a once-only principle where governments aim to reduce the amount of information citizens need to provide to public authorities.

A digital public infrastructure approach

[CITY] can take steps toward improving its data exchange capabilities by exploring the development of a data exchange approach across the organisation or region. As part of digital public infrastructure (DPI)—the shared capabilities needed to participate in society and markets—better data exchange can enhance service delivery and decision-making. Without a foundational infrastructure layer to facilitate secure and efficient data sharing, public institutions often rely on siloed agreements and manual file transfers.

Cities can learn from models like Estonia’s X-Road and Uganda’s UGhub, which enable secure inter-agency data exchange while maintaining privacy and decentralisation. These approaches allow organisations to share data without centralising it in a single repository. By gradually adopting standardised protocols and governance mechanisms, [CITY] can move toward a more connected data ecosystem, improving services while strengthening public trust.

Data custodians, owners and custodians

In order to implement the data strategy both direct and transversal resources are required. These include:

- Data Stewards: Tubject experts with a thorough understanding of a particular data set. The Data Steward of a data resource is responsible for ensuring the classification, protection, use, and quality of that data, in line with the Data standards set by the Data Owner. Data stewards may exist in departments and agencies or operate more centrally, and are fundamentally responsible for the use of data within an organisation. Data stewards typically support data owners.

- Data Custodians: A Data Custodian is responsible for implementing and maintaining security controls for a given dataset in order to meet the requirements specified by the Data Owner. This is typically an IT or IMU role.

-

Data Owners: The person accountable for the classification, protection, use, and quality of one or more data sets within an organisation. This responsibility involves activities including, but not limited to, ensuring that:

- The organisation’s Data Catalogue is comprehensive and agreed upon by all stakeholders

- A system is in place for auditing and reporting data quality

- An escalation matrix is in place for data quality issues

- Actions are taken to resolve data quality issues within a defined timeframe

Data Equity

To ensure data equity, [CITY]’s data infrastructure must support:

- Disaggregated data collection and standardisation:

- Incorporate demographic indicators (e.g., gender, disability, socioeconomic status) into foundational datasets.

- Adopt open standards that facilitate cross-sector data sharing on social disparities.

- Ensure that API standards allow for accessibility and inclusivity in datasets.

- Open Data for Equity & Accessibility:

- Prioritise the release of public datasets that support social equity research and advocacy.

- Provide alternative data outputs, such as data stories, for persons with disabilities and low digital literacy. Examples of alternative outputs could be audio, simplified text, local languages.

- Community-Based Data Integration:

- Recognise community-driven data as valid inputs for municipal decision-making.

- Build trusted mechanisms to incorporate community-collected data into formal governance processes.

Action Items

- Publish a foundational data catalogue, starting with the top 25 datasets

- Design and test a single process adopting open standards for data and identifiers

- Conduct assessment of [CITY]’s current data infrastructure

- Define the responsibilities of a data custodian to support transversal outcomes

- Design and test a single process for departments to request access to data from other departments

- Develop a plan to move towards the safe implementation of the ‘once-only principle’

- Assess all new data projects and procurement of data tools against the data standard

- Appoint a Gender, Equity and Social Inclusion (GESI) specialist placed at the CDataO team